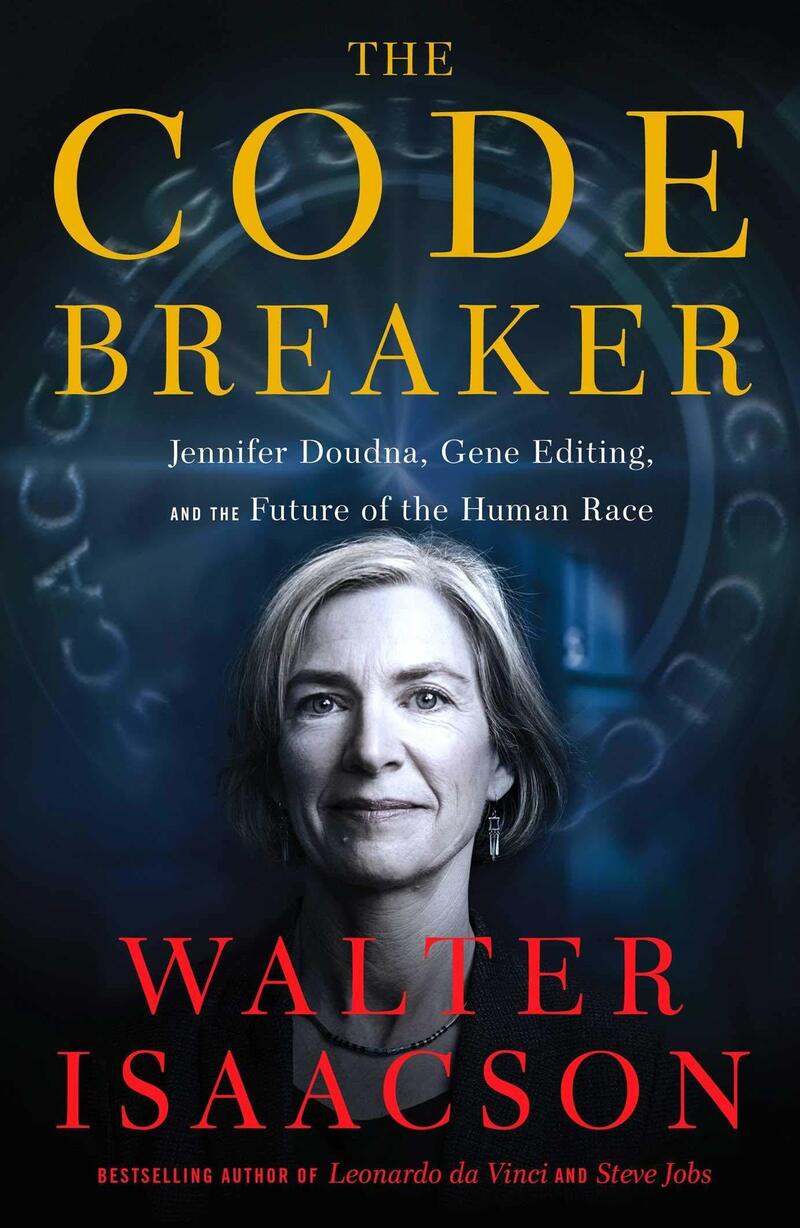

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race, Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster

hide caption

toggle caption

Simon & Schuster

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race, Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster

In early November 2018, twin girls — Lulu and Nana — were delivered by caesarian section in a Chinese hospital. Their birth probabably would have gone unnoticed outside of the family except for one factor: They were the world’s first gene-edited babies.

A Chinese scientist, He Jiankui, edited their embryos ostensibly in an effort to protect them from being infected with the HIV virus, using a gene editing tool called CRISPR. The announcement of designer babies was met with horror and outrage, particularly in the scientific community. He lost his job and was sentenced to three years in prison.

These potential, and far-reaching, consequences of gene-editing technology are themes running through Walter Isaacson’s new book The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race.

Coming in at nearly 500 pages, the book dives into the essence of life and the heady world of genomes and genetic coding, or what Isaacson calls “the third great revolution of modern times,” following the atom, and the bit which led to the digital revolution.

For the uninitiated — those folks who cannot tell their DNAs from RNAs — understanding this new frontier in science can be a bit daunting. Take this example early on in the book when Isaacson explains the difference between the two:

“RNA (ribonucleic acid) is a molecule in living cells that is similar to DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), but it has one more oxygen atom in its sugar-phosphate back bone and a difference in one of its four bases.”

Isaacson makes it clear that RNA has played a starring role both in The Code Breaker, as well as in the life and career of its central character, Jennifer Doudna, who was the co-recipient of the 2020 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for the discovery of CRISPR, the gene-editing technology.

CRISPR is the unwieldy acronym for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, which is essentially a natural way of altering or replacing DNA sequences in a cell. It is being tested in food and animals and, in a limited way, to correct or treat genetic defects such as sickle-cell anemia.

Like his earlier books on Steve Jobs, Leonardo da Vinci, and Albert Einstein, Isaacson leans heavily on profiles to tell the broader story. In this case, he focuses on Doudna (pronounced DOWD-nuh) to explore the confluence of science, innovation, and ethics.

Doudna was raised in Hawaii where with blonde hair and blue eyes she says she felt like “a complete freak.” But she loved exploring nature in the surrounding meadows and sugarcane fields, and was encouraged by her father and a biology professor to think about a life devoted to science.

That interest was ignited when her father gave her a battered paperback copy of James Watson’s The Double Helix, a lively account about the discovery of the structure of DNA for which he won a Nobel prize in 1962, along with fellow biochemists Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins.

Isaacson passionately charts Doudna’s swiftly rising star, as she moves from labs and schools, including Harvard and Yale, ultimately ending up at the University of California, Berkeley where she heads the Department of Chemistry and the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology.

But Isaacson also pays tribute to the many others who, in their own way, contributed to the understanding and development of gene editing, by weaving in compelling vignettes along with glossy photos of scientists and researchers. It’s a broad cast of characters, and at times the choice seems a bit random. But, ultimately, it helps create an understanding that these breakthroughs are not created in a bubble, it requires a patchwork of experiments and expertise over many years.

The mini-biographies also highlight the interpersonal relationships and rivalries among the scientists. It was eye-opening to read of the ferocious competition, backstabbing and underhanded efforts that can go on as scientists and researchers attempt to get papers published first, win prizes, or obtain patents that can bring in billions of dollars to a college. More than once Isaacson questions whether science suffers in the race for glory.

Isaacson doesn’t hold back about Doudna’s own strong competitive streak, or her ongoing competition with Feng Zhang, a China-born researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT. Over the years the two have been locked in legal battles over patents.

But there is also collaboration amongst scientists when the need arises, as was the case in 2018. The birth of the gene-edited babies in China was a clarion call for the scientific community at large. It was seen as crossing a red line. Gene editing to battle sickle cell enema was one thing, using the technology in the hopes of making babies taller, smarter, free of any disease was another.

Since then, Doudna has become the face of the ethical dialogue surrounding the potential of CRISPR technology — speaking widely, including to Congress, about the promise and the serious, even dangerous, implications if this powerful technology.

Isaacson wraps up on a positive note, adding a final chapter on the role of CRISPR technology in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, helping to detect the RNA of the coronavirus.

In the epilogue, Isaacson admits to what becomes abundantly clear throughout the book — that he too read The Double Helix when he was young and, like Doudna, wanted to become a biochemist. He didn’t. Instead he chose a profession that gives him a prime seat to view this new scientific horizon.