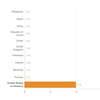

President Biden looks on after speaking during an event about gun violence prevention in the Rose Garden of the White House on April 8.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

President Biden looks on after speaking during an event about gun violence prevention in the Rose Garden of the White House on April 8.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

When an assailant stormed a grocery store in Boulder, Colo., last month and fatally shot 10 people, the suspected weapon of choice — a Ruger AR-556 pistol — captured immediate attention. Not for what it technically was — a pistol — but for what it more closely resembled — an assault-style rifle.

The legality and lethality of semi-automatic “assault-style weapons” has been a topic of debate before. But in the wake of the mass shooting in Boulder, calls are once again growing for a federal ban on these guns, including from President Biden. While unveiling a series of new measures around gun violence prevention at the White House on Thursday, the president said the nation should reinstate a version of the federal assault weapons ban he helped to pass as a senator in the 1990s.

That legislation, the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994, was signed into law by President Bill Clinton in the shadow of mass shootings like the 1989 Cleveland Elementary School shooting in Stockton, Calif. Designed to last for a period of 10 years, its intended effect was to bar the sale of semi-automatic weapons and large capacity magazines to civilians.

The bill, while admittedly flawed even to its cheerleaders, set a model for proponents of banning high-power firearms from civilian hands. As advocates today look to overcome steep odds to bring the ban back, they are hoping to avoid a repeat of past mistakes.

“I think one of the issues that came up with the original Assault Weapons Ban of ’94 was that lawmakers underestimated maybe the creativity of a gun industry intent on circumventing the intention behind these laws,” said Christian Heyne, vice president of policy at the gun safety organization Brady.

Part of the problem then, and now, is the difficulty in formally defining what exactly constitutes an assault weapon. The 1994 bill relied on banning firearms by name and certain specific characteristics, largely ignoring function and how easily certain guns can be customized. Those loopholes allowed manufacturers and hobbyists alike to retrofit firearms with modifications that made the guns largely indistinguishable in function from their prohibited counterparts.

“The gun industry spent really that entire period of finding ways to circumvent these policies that are in place to make sure that the weapons that are being sold in the civilian market are not the same weapons designed for warfare,” Heyne said.

The 1994 bill expired in 2004 under President George W. Bush.

A new bill, the Assault Weapons Ban of 2021, introduced by Rep. David Cicilline, D-R.I., and Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., hopes to address the shortcomings of its predecessor. The bill prohibits the sale, manufacture, transfer and importation of 205 “military-style assault weapons” by name, and bans magazines that hold more than 10 rounds of ammunition. It not only prohibits a greater number of weapons than the original law, but would also make it harder to retrofit them.

The bill would not affect gun owners already in possession of these weapons on the date of enactment, and it exempts more than 2,200 firearms of “hunting, household defense or recreational purposes,” according to a synopsis of the bill.

The effect of the ban

While the original ban’s impact on overall crime appears to have been negligible, research has shown that during the 10-year period it was in effect, it likely contributed to a decrease in the number of fatalities associated with mass shootings — defined as an incident in which four or more people are injured in one event.

A 2019 study led by New York University School of Medicine professor Charles DiMaggio, for example, found that fatalities were 70% less likely during the period of the ban.

“We did see fewer mass shootings during the period of the ban compared to the periods before and after it was in effect,” said Adzi Vokhiwa, federal affairs director at Giffords, a gun safety and advocacy organization.

“But I think the big problem we saw with the previous iteration of the assault weapons ban was that it didn’t address weapons that were already out in circulation in a strong enough manner,” Vokhiwa said. “And that’s why we think any potential ban on assault weapons that addresses future production of those weapons also needs to address the weapons, which by some estimates are in the tens of millions, that are already out in civilian hands.”

Her policy prescription would be to regulate semi-automatic weapons the way the United States does machine guns and silencers under the National Firearms Act — that is to require owners to undergo a background check and have them filed to a national registry or risk confiscation of those firearms.

Second Amendment challenge

This notion — the possibility of gun confiscation under the passage of such a ban — has been the biggest stumbling block for gun safety advocates and lawmakers.

Opponents of the ban argue that any additional restraints to the gun industry constitute a violation of the Second Amendment. And the prospect of gun confiscations is almost unspeakable in most all gun rights circles.

“I’ve never been more worried about an attack on the Second Amendment than I am right now,” Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said earlier this month during remarks opposing an assault weapons ban.

“One of the things about our Constitution is that we understood early on that if you live in a dictatorship, or in places where the government runs everything, the first thing they take away from you is not just your speech, but your ability to defend yourself. That’s why the Second Amendment exists. The ability to own a gun responsibly is a constitutional right in America, and here’s what I would say: we need that right today, as much as any other time in American history.”

While confiscation might be the eventual goal of some in the gun safety community, Rhode Island Rep. Cicilline, one of the authors of the 2021 bill, said a mass gun grab is not his focus nor that of any of his colleagues.

“We have to just beat back the misinformation from gun enthusiasts who think any effort to reduce gun violence in this country is an effort to take their guns,” Cicilline said. “This idea of a slippery slope … it’s just not true.”

Cicilline said he is hopeful Congress can make meaningful movement on gun safety laws now that Democrats control both chambers and there is a Democrat in the White House.

“We have to respect people who are gun owners. We have a right, too, to ensure that people can live a life free from gun violence,” Cicilline said.

Prospects in Congress

President Biden has long expressed support for a modern assault weapons ban — a sharp departure from his predecessor, who strongly embraced the most conservative interpretations of the Second Amendment. In his remarks at the White House this week, Biden unveiled a series of executive actions, including an effort to rein in so-called “ghost guns,” which can be assembled at home and contain no serial numbers. Biden said his actions were meant to curb what he called the nation’s “international embarrassment” of gun violence.

“This is an epidemic for God’s sake, and it has to stop,” Biden said.

“Enough prayers,” he said. “Time for some action.”

Despite holding a slim majority in both chambers, Democrats still face an uphill battle in the fight to strengthen the nation’s gun restrictions.

Any bill that makes its way through the House will face strong opposition in the Senate, where Democrats would need full party support and to secure at least 10 GOP votes to break any Republican-led filibuster.

The House has not passed a bill on banning assault weapons, but already two bills aimed at gun safety — both focused on background checks for gun sales — seem stalled in the Senate.